A formidable fiber of my relationship with the land is entangled through academic research. I began my conservation environmental degree without a clear career goal, but the curiosity and longing I intuitively felt kept me committed to the linear university pathway. By the end of my degree, I was torn. I narrowed my interests, job applications, and letters to graduate school advisors to the camps of oceanographic studies or terrestrial studies. And after I held my diploma, the anguish of making a decision grew.

Until one day, I decided my choice was to forego deciding all together.

Not giving up.

Acknowledging.

I wanted to acknowledge my graduation journey and enjoy the milestone before moving onward.

I wanted to breathe.

The crisp winter air before spring’s bounding growth.

A few days after letting go I received a phone call from the Wisconsin DNR research department, asking if I wanted to interview and subsequently accept a position on their Dendrochronology and Fire Ecology research team.

Maybe we could say that the land chose me.

Or maybe my ‘being’ was so grounded in the land that I longed for the depths of the ocean.

I think my heart and mind will always long to explore the benthic zone of oceans, lakes, and streams.

I also think my heart and mind truly belong elsewhere.

To longing.

But they're both mine today.

And I have staunchly loved belonging and exploring the land predominantly for the last six years.

Periodically I like to revisit or study research periodicals.

To help shift my focus and understandings.

This one has had an everlasting impact on my view of urban and suburban aesthetics, as well as how my neighbors may view their connection to the land.

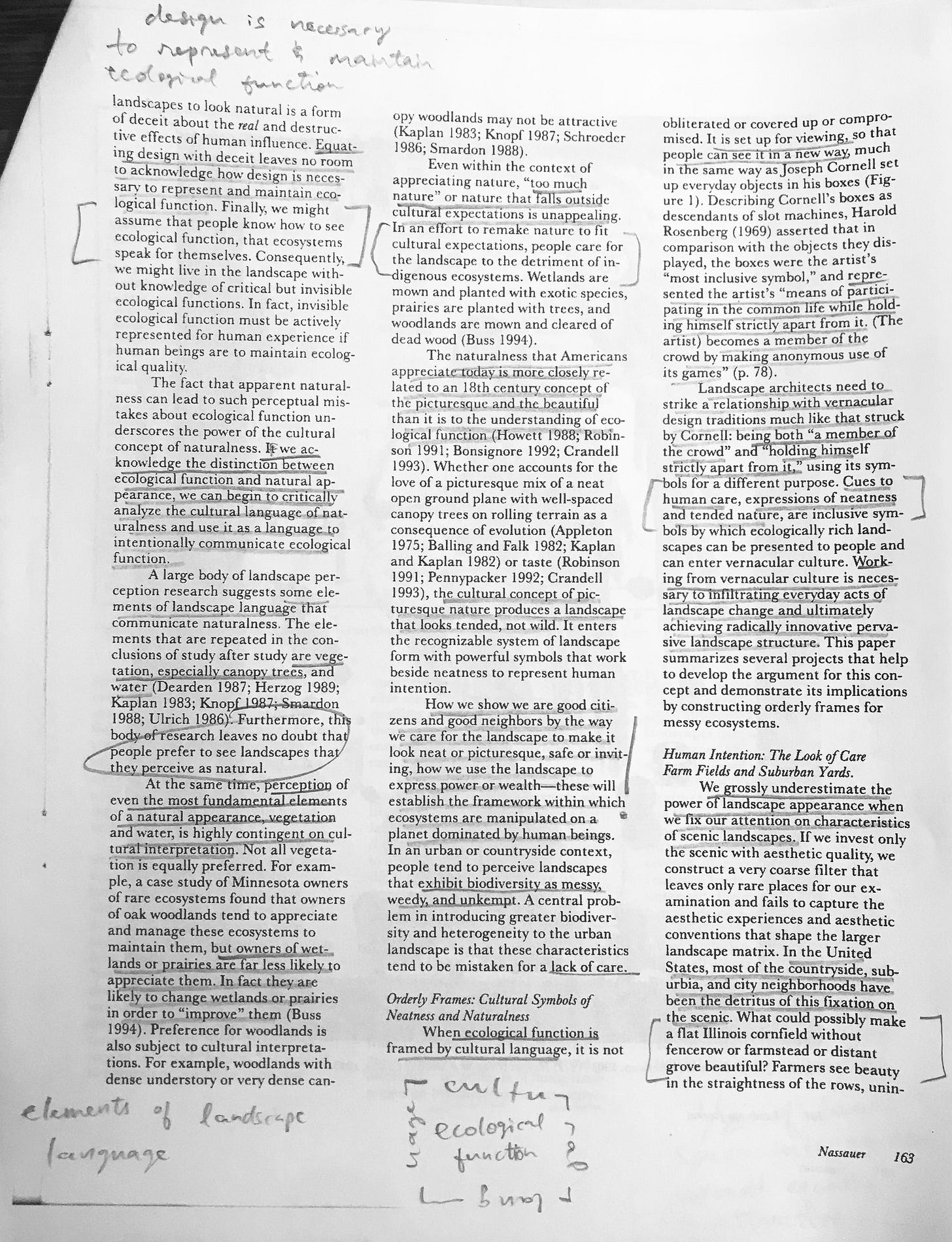

I am a big fan of dog ear-ing pages, writing in the columns, and bookmarking my readings.

So I print off a copy with my laser printer.

Sharpen my pencil.

And I make notes on the pages.

Below is a quick abstract from the journal.

From 1993 and pertains still today.

Based in the Twin Cities.

From Professor and Landscape Architecture Department Head Joan Iverson Nassauer.

Some thoughts and questions of mine follow.

An appropriate, ‘extra’ New York Times article follows that.

It revolves around a state law in Maryland affecting/protecting land usage at the level of homes and communities.

Seriously, I would encourage you to read and think about this topic at large.

But if you wish not to, then just take a moment where you live.

Observe.

What your typical neighborhood yard looks like.

How the city has/lacks overstory trees.

Why your neighbor insists on spending so much time, energy, resources on an empty carpet of green.

Who your other neighbor is, the one that does not even care at all.

Where you explore freely and find new vegetation or curious life forms.

Where you draw inspiration from.

Keep observing.

It is a subject that is often glanced over or internalized, but guides how we interact with our surroundings and neighbors on a day to day basis.

What is life but a string of days, stitched together by others and our own longing and belonging?

Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames

By Joan Iverson Nassauer

Abstract:

Novel landscape designs that improve ecological quality may not be appreciated or maintained if recognizable landscape language that communicates human intention is not part of the landscape. Similarly, ecologically valuable remnant landscapes may not be protected or maintained if the human intention to care for the landscape is not apparent. Landscape language that communicates human intention, particularly intention to care for the landscape, offers a powerful vocabulary for design to improve ecological quality. Ecological function is not readily recognizable to those who are not educated to look for it. Furthermore, the appearance of many indigenous ecosystems and wildlife habitats violates cultural norms for the neat appearance of landscapes. Even to an educated eye, ecological function is sometimes invisible. Design can use cultural values and traditions for the appearance of landscape to place ecological function in a recognizable context. I describe several examples of cultural language “cues to care” that provide a cultural context for ecological function, and I demonstrate how these cues can be used in design.

© 1995 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

My biggest takeaways were:

The problem requires the translation of ecological patterns into cultural language “…but a public landscape problem of addressing cultural expectations that only tangentially relate to ecological function or high art. It requires the translation of ecological patterns into cultural language.” (Eaton 1990 a,b) THIS was the breakthrough for me. THIS is what I would like to devote more time and energy to. THIS is why I do what I do. THIS is my purpose.

Perception of human intention, what are further design cues of human intention? What happens if we intentionally avoid or rebel against these cues as an individual or as a community? These were the design cues mentioned: Mowing, Flowering Plants and Trees, Wildlife feeders and Houses, Bold Patterns, Trimmed Shrubs/Plants in Rows/Linear Planting Design, Fences/Architectural Details/Lawn Ornaments/Painting/Foundation Planting.

Design is necessary to represent and maintain ecological function. As I like to say, “Function is the most important. Aesthetics always come second, although they are equally as important.” The reasons being, if Aesthetics were more important, the (blank) would be hollow and not practical. If Functionalities were more important, the (blank) would lack human expression and sensibility. As I see it, we need humans to be engaged in order to care for things, or who else will take care and put energy into an unbalanced system?

What are elements of landscape language? And how does the language change with time? Does the language change with communities or is there a universal language we can understand and communicate with, if not in America then at least in the Midwest?

1/2 of lawn space into garden is almost equally attractive as conventional landscape treatment (all mown turf lawn). This was a study done with 234 residents in a Twin Cities suburb in Minnesota, 1993. Would this finding be altered with the passing of 30 years?

“Too much” trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses loses the immediate cues to care, the presence of human intention. If there is a legible design concept that can frame the “too much” in, does it then regain the cues to care? Or is it still sensory overload for most?

How do other humans look at scale and legibility with the land?

Extra Reading Opportunity:

New York Times Article

‘They Fought the Lawn. And the Lawn’s Done.’

After their homeowner association ordered them to replace their wildlife-friendly plants with turf grass, a Maryland couple sued. They ended up changing state law.

My wish to you.

May you find and hold warmth as long as you’d like,

-moki-

¯\_(ツ)_/¯¯\_(ツ)_/¯¯\_(ツ)_/¯